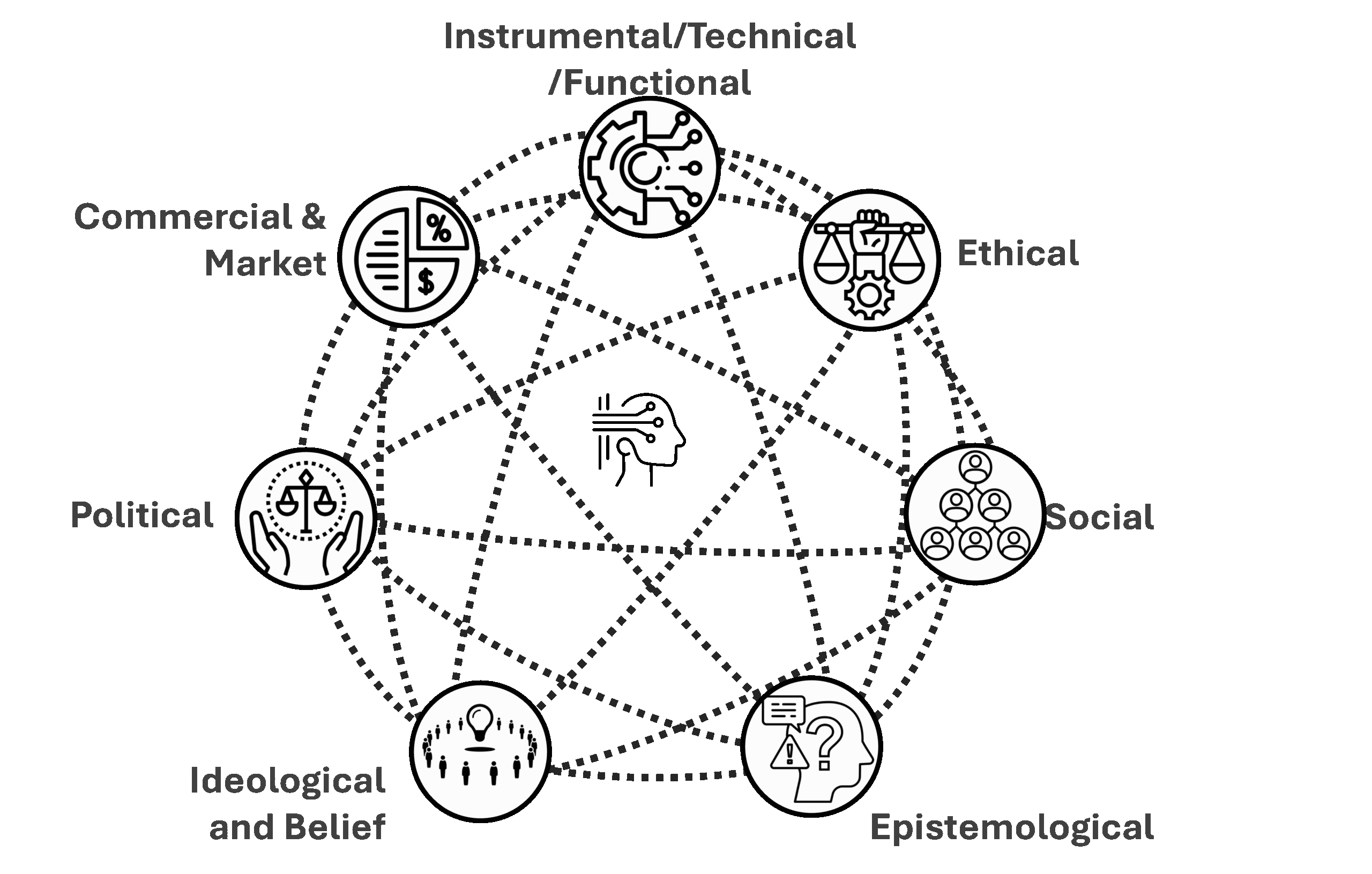

Two new texts have finally been published (you’ll find them at the end of this post), where together with Ana Yara Postigo-Fuentes and Amaia Arroyo-Sagasta we explore the analysis of AI from a prismatic perspective. In these works, we argue that AI—as an educational technology—should be understood through a framework that includes at least seven dimensions: instrumental, ethical, epistemological, ideological, political, social and commercial.

When Ana Yara, Amaia, and I use the prism metaphor, we do so because, in optics, a prism not only refracts light—it decomposes it and reveals its invisible components. Likewise, thinking of technology as a prism, rather than a simple lens, allows us to understand that its role in education is not merely to transform what we do, but to make visible the multiple dimensions that constitute the “white light” of educational practice—dimensions often assumed or even deliberately ignored. From a postdigital and phenomenological perspective, the technological prism does not act as a filter but as a space of revelation and tension: it confronts us with the complexity of the educational, allowing us to analyze, reinterpret, and reconfigure its different layers—including the instrumental one—alongside others that often remain hidden.

However, using a metaphor can sometimes blind you to the very tensions that the metaphor itself carries. That’s why I’d like to use this space to offer a brief critique of our own metaphor, because I think it contains a few conceptual tensions and what we might call “points of potential contradiction” — or, perhaps better said, optimistic assumptions. Let’s take a look:

- The Implicit Neutrality of the Prism (the Problem of the “Neutral Artifact”): The metaphor presents the prism as a neutral instrument that simply “reveals” a pre-existing truth. Yet technology is not neutral. While a glass prism has fixed physical properties and its effect on light is predictable and universal, our argument precisely rests on the idea that educational technology—and AI in particular—is value-laden, shaped by ideologies, commercial interests, and specific designs. Therefore, the technological prism not only “reveals” dimensions; it also configures and creates new ones.

- The Assumption of a pure, pre-existing “White Light”: The metaphor assumes that there is a “white light” (educational practice) that is pure and coherent before passing through the technological prism—and that’s false. Educational practice is never that pristine white light; it is always already mediated by its sociomaterial nature. The very idea of an educational essence that precedes technology is precisely what the postdigital perspective questions. For that reason, the technological “prism” does not intervene in a pure practice; it has always been constitutive of it. The metaphor must not be read as implying that technology arrives later to an innocent practice—because that would reproduce the very simplistic view of education we aim to challenge.

- The Optimism of “Revelation” The prism metaphor is not meant to suggest that technology—or AI—by itself “reveals,” “makes visible,” or “creates spaces of revelation.” Rather, we should understand the complexity of what it affects (the light). The point is not that technology is an agent of revelation, but that the metaphor of the prism offers a critical framework to examine how, once introduced, technology makes visible the tensions and dimensions that were previously entangled within educational practice. Revelation is therefore an achievement of analysis, not a property of the tool.

It’s important to remember that this image—one that we like very much (I admit, I love it! 😄)—is a powerful but partial metaphor. It highlights certain aspects (complexity, multidimensionality, analytical potential) while obscuring others (non-neutrality, opacity, and the constitutive nature of techne). Its purpose is to shift the conversation away from mere instrumentalism (“how to use a tablet”) toward a deeper reflection (“what the tablet does to our understanding of education”). Yet its rhetorical strength may rely on a view that is perhaps too benevolent toward the role of technology.

So… does that make it invalid? Not at all. I genuinely believe that the prism metaphor offers a conceptual framework to begin a critical discussion—but that critique must start by deconstructing the optimistic assumptions within the metaphor itself. Its value does not lie in being a “truth,” but in serving as a productive catalyst for thought.

For those who’d like to read the full texts and think along with us, here they are:

- Castañeda, Linda; Arroyo-Sagasta, Amaia & Postigo-Fuentes, Ana Yara (in press). When Digital Literacy Must Go Beyond the Screen: Further Dimensions for Analysing the AI Impact in Education. In Flynn, N., Garcia, P. O., Joseph, H., Powell, D., & Slater, W. H. (Eds.) (in press). The Bloomsbury International Handbook of Literacy. London, UK: Bloomsbury Press.

- Castañeda, Linda; Postigo-Fuentes, Ana Yara & Arroyo-Sagasta, Amaia (2025). Beyond Tools, Toward Power Structures: A Critical Review of AI in Primary Education. Revista Española de Educación Comparada (48), 73–95. https://doi.org/10.5944/reec.48.2025.45126